The Marchant Family

Captain Christopher Marchant, my 8th great grandfather, was a French Huguenot, who made his fortune as a privateer. When he wasn’t aboard ship, he held many political and legal positions in Currituck County North Carolina: council member, clerk of council, custom collectors, clerk of precinct court, deputy escheator (the officer in charge of property transfers for those who died without wills). In his will written in 1698 he gave his daughter Abiah a gold ring, his son-in-law Thomas Tooley 20 pounds, his son Willoughby Marchant his sword and belt, his gold and silver buttons and buckles and his “prized priveteer gun.” His estate which included a 908 acre plantation was to be divided was to be divided between his wife, Abiah Bryan Marchant, and son Willoughby (who was still a minor) and should they “be in want of servants or any other necessary supplyes” they had permission to sell his lands. His wife’s brother, Richard Bryan, was placed in charge of overseeing all business affairs for the family.

Willoughby Marchant (1675-1727), my 7th great grandfather most likely followed in his father’s footsteps because he was also referred to as “Captain”. He also served his community as a justice of the peace and as a sheriff. He married Elizabeth Corbett and had seven children one of whom, my 6th great grandfather, was named Gideon Marchant I (1710-1774).

[Photo: Rigging of an Antique Ship]

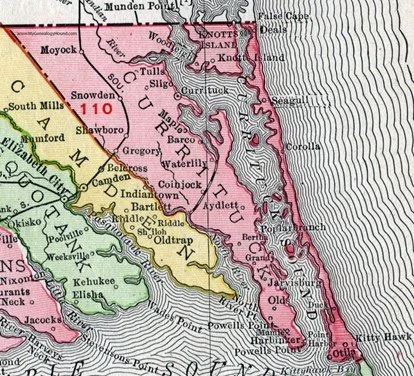

The home of the Marchant family, Currituck County, is sandwiched between the Albemarle Sound and the Currituck Sound and separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Outer Banks. If you made your living on the seas, it was the perfect place to call home. It was founded in 1668 and named by the Algonquian nation whose translation means “Land of the Wild Goose, ” which feels oddly appropriate. Today Currituck is it is home to the largest horse population of Banker Mustangs, which are said to be descendants of Spanish expedition if the 1500s.

One account written in 1712 made this observation about North Carolina:

“Of all the thirteen colonies, North Carolina was the least commercial, the most provincial, the farthest removed from European influences, and its wild forest life the most unrestrained. Every colony had its frontier, its borderland between civilization and savagery; but North Carolina was composed entirely of frontier. The people were impatient of legal restraints and averse to paying taxes; but their moral and religious standard was not below that of other colonies. Their freedom was the freedom of the Indian, or of the wild animal, not that of the criminal and the outlaw.”

Photo: [Map of Currituck]

A pirate terrorizes and pillages merchant ships. A privateer is essentially a pirate who legalizes this lucrative activity by obtaining the blessing (“letters of marque”) from a government during war times. The line between the two can become blurred. Many famous pirates including Blackbeard and Captain Kidd started as privateers and then “turned to the dark side” - piracy. Privateering can be traced back as early as the 13th century. It played a very important role in the American Revolution.

[Photo: Painting of Pirates by Gregory Manchess]

The Continental Army was comprised of 63 ships, and it commissioned 1500 privateering vessels with 55,000 sailors to assist in their cause. To my surprise, the use of privateers is actually enshrined in the US Constitution. Privateering fell out of favor after the War of 1812 and reappeared briefly during the American Civil War. Rhett Butler from the famous southern saga “Gone with the Wind” made his fortune that way. All major powers in Europe abolished privateering in the Declaration of Paris 1856. America and Spain refused to sign. The practice officially ended in 1907 when the US finally agreed to make privateering illegal. A year later Spain followed suit.

When Gideon Marchant I died he left his oldest son Malachi “the whole plantation whereupon I now live and four ewes and lambs,” his son Gideon II inherited “two negro boys called Sam and Antony, two negro girls named Area and Juda them and their increase to him and his heirs, a feather bed and furniture.” Two of his daughters Priscilla and Frankey each inherited “two negros and one feather bed.” His third daughter Betty Woolard also inherited two negros but not a feather bed because as a married woman presumably she already had a place to sleep. The rest of his estate was to be sold and equally divided between all of his children except for Malachi and Betty was not to receive the proceeds from the sale of his cattle.

Malachi married Lydia Reed, and they had two children Edney and Jordan. When Malachi and Lydia passed away their teenaged son Jordan was placed under the guardianship of his uncle, Gideon II. At the age of 27 Jordan married a widow Fanny Shields (Shepherd) and the couple had five children between 1798 and 1808. He served in the Virginia Militia and was a Justice of the Peace for Norfolk County. Jordan spent the evening of November 11, 1811, enjoying himself at the horse track. As he was crossing the drawbridge on his way home he was attacked and murdered, his body tossed in the river. He left behind his heartbroken wife (now widowed for a second time) with six children the youngest of whom (his namesake Jordan) was only two years old. Neither the cause of the murder nor the person who or persons who perpetrated the crime has ever been determined.

[Photo detail: Map of the harbor where Jordan Marchant was murdered]

Shortly after the murder, a man by the name of Miles was arrested along with three others who were suspected of possibly being involved in the murder. Miles was discharged for lack of evidence. An angry mob formed on Saturday the 16th, marched to poor Miles’ house, forcibly removed him from his home and took him to the draw bridge where the murder had taken place. The mob tarred and feathered him, tied a cord around his waist and dragged him through the streets of the town. My jaw dropped when I read this. I thought this kind of torture was a relic of the past.

Tarring and feathering is a form of public torture where a victim is stripped, drenched in hot tar or other sticky substances, covered with feathers, and then dragged through the streets to accentuate their public humiliation. Although the hot tar is extremely painful it is not fatal. This cruel practice originated in medieval times and was apparently quite popular during the American Revolution for punishing loyalists and tax collectors. Recorded cases of tar and feathering in the US occurred well into the 1900s. In 1930 five brothers from Louisiana were arrested for tarring and feathering a prominent dentist, in retaliation for the dentist having an affair with one of the brother's wives. And here’s a shocker in 1971 a Michigan high school teacher principal named Wiley Brownlee was kidnapped by the KKK and tarred and feathered for speaking at a school board meeting in favor of honoring Martin Luther King.

[Photo: Tarring and Feathering in Colonial Times]

Gideon Marchant II married a woman named Catherine and named their son Gideon Marchant III. Gideon III like his father’s before him was a Sea Captain and Master of a ship, named Polly. Gideon III married a woman named Mary and they had at least three children, Gideon C Marchant IV (1798-1861), Johnson and Polly (perhaps after his father’s ship). Gideon III died in 1812. A year after his death, his wife remarried Lemuel Wilson and turned over her claim to Gideon’s estate to her three children but reserved for herself “the use of one horse and harness and one negro woman named Lettice until my daughter Polly shall marry and one negro man in case I am widowed for a second time.” Gideon IV broke tradition and became a doctor.

Dr Gideon C Marchant IV, the son of Gideon and Mary Marchant III, was born in 1798 in Virginia. Dr. Marchant’s life reminds me of a memorable scene from the movie “The Graduate.” He fell head over heels with Margaret Elizabeth Ferebee and asked his beloved to be his wife. Her father, Thomas Cooper Ferebee, a very prominent man in Currituck County was not thrilled with the arraignment and persuaded her to marry a well to do neighbor instead. Gideon was at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in May of 1817, when he got the gut wrenching news that his fiancée was to marry someone else. He raced home, buying and exhausting five horses on the way from Philadelphia to “Culong”, the Ferebee Plantation in Currituck. When he got there the wedding guests were just starting to arrive. Gideon asked one of the Ferebee’s enslaved persons to tell his fiancée he had come for her. Emily escaped out the back door, joined Gideon atop his gallant steed, and they rode away to get married, leaving the bridegroom and the guests in shock. Unfortunately their happiness was short lived. Emily died in 1823 without any children.

[Photo Detail: Culong Plantation on Indian Town Road built 1812]

Five years later in 1829, Gideon married the widow Emily Dauge Trotman, and the couple had two children: Elizabeth Ferebee and Archann Dauge. The doctor and his wife lived on a plantation nestled in over 700 acres of land known as Indiantown Plantation on a road bearing the same name. It has been described as one of the finest in the Albemarle area. It was a village with twenty or more buildings connected with brick walkways. Gideon was quite wealthy. The 1860 Currituck County census lists his real estate at $30,000 and his personal estate at $50,000.

Gideon died in 1861 followed shortly after by his wife; “after having been married for more than 30 years in life – were separated in death but by the brief space of three days.”

After their deaths, the Civil War spilled onto their property and his house all of their buildings were burned down. Fallen Civil War soldiers as well as Native Americans from colonial times are buried in Gideon’s back yard. Today his medical equipment is on display at the Museum of Albemarle in Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

Gideon’s daughter, Archann Dauge Marchant married my 2nd great grandfather Durant Hall Tillitt.

[Photo Detail: Dr Gideon C. Marchant and Emily Dauge Trotman Marchant’s tombstone ]