The Caldwell and Rodgers Family

In 1534 John Rogers traveled to Antwerp, Belgium to serve as a chaplain. There he met the celebrated William Tyndale, a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation, who convinced John to abandon his faith in the Roman Catholic Church. William translated the New Testament into English from Hebrew and Greek texts and created the first English translation of the bible to use a printing press in 1526.

William felt everyone should be able to read the Bible in their own language, directly challenging the authority of the Catholic Church that maintained control over biblical interpretation. He fled from England to Belgium to escape persecution; and was betrayed, imprisoned and executed there in 1536.

John took up the cause where William left off, publishing the Bible under the pseudonym “Matthew’s Bible” in 1537. For his efforts he was imprisoned in the notorious Newgate Prison in London to be “lodged among thieves and murderers and very uncharitably treated.” He refused to “revoke his abominable doctrine” and in 1555 was burned at the stake.

[Photo: John Rogers 1505-1555 Bible Translator and Martyr]

His wife came to the execution with all eleven of his children in tow with one “suckling at her breast” perhaps to offer support; perhaps to compel him to speak the words that would prevent his cruel death. But he would not give in. In so doing he became the first of 280 religious dissenters to be executed as “a heretic” in England under the rule of Bloody Queen Mary I.

A copy of this ancient Matthews Bible can be found today at the Museum in Washington D.C. and several other museums across the country.

[Photo: The Matthew Bible published in 1537 by John Rodgers]

The next six generations have been meticulously documented. John Jr (1548-1601), who would have been seven years old when his father was engulfed in flames, did not go into the ministry. But the next four generations did. There was the Rev. John Rogers (1548-1601), followed by the Rev. Nathaniel Rogers (1598-1655) who landed in Boston in 1636, followed by the Rev. Dr. John Rogers who was a minister, a physician and the fifth President of Harvard University, followed by the Rev. John Rogers of Ipswich Massachusetts (1666-1745), followed by William Rogers (1697-1750) born in Massachusetts and travelled to Virginia where he married Margaret Caldwell, the daughter of John Caldwell and Margaret Phillips, followed by a son Thomas who was born in 1725.

Unfortunately, according to extensive research by my mother, this is not correct. William Rodgers (my 6th great grandfather) is not part of that family tree. The Rogers family that descended from John the Martyr belonged to the Church of England but William was a Presbyterian. All of William’s other alleged brothers, John, Nathaniel, Richard, Daniel, and Samuel graduated from Harvard, William did not. William’s alleged son Thomas was born in 1725 but this could not be their son because Margaret Caldwell did not arrive in America until 1727. Our ancestor William spelled his name Rodgers with a “d” which was the spelling used in Scotland. John the Martyr was born in England. Unfortunately there is no solid connection between our William Rodgers and the John Rogers the Martyr powerhouse genetic pool. I located a headstone which stated: “John Caldwell I (1682-1750) and his wife Margaret Phillips (1685-1748), both born of Scottish parents, emigrated from Derry, Ireland and landed in America at Newcastle Delaware on December 10, 1727.” A memorial plaque says John convinced the Governor of Pennsylvania to provide a large 30,000 acre land grant in Virginia which became known as the Caldwell Settlement on Cub Creek, a colony for Scots Irish Presbyterian “dissenters”. We might not be connected to The Martyr but the Caldwell family was quite the powerhouse in their own right and there is conclusive evidence that they are connected to the Rodgers family. John Caldwell and Margaret Phillips are my 7th great grandparents.

John Caldwell and Margaret Phillip’s oldest son, Major William Findley Caldwell (1704-1761), married Rebecca Park, and fought in the French & Indian War. William’s daughter, Martha, married Patrick Calhoun and their son, John Caldwell Calhoun, became a South Carolina statesman and served as Vice President under John Quincy Adams. Calhoun was a fiery advocate for state’s rights and slavery. The owner of 70 to 80 enslaved persons, his beliefs heavily influenced the South’s secession from the Union.

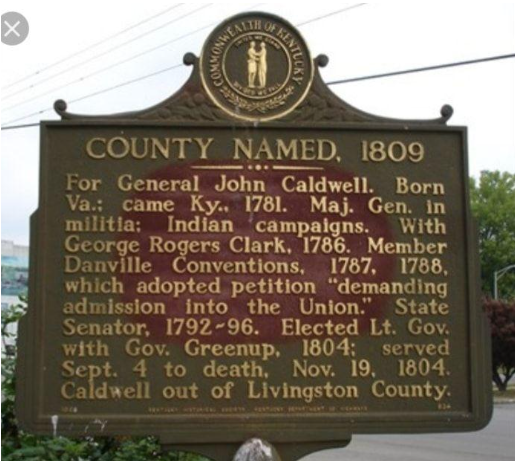

John Caldwell and Margaret Phillip’s son Robert (1732-1806) served in the Revolutionary War. He had a son General John Caldwell, a veteran of the Kentucky Indian War of 1786, who became the 2nd Lt Governor of Kentucky in 1804. While presiding over the state senate John died from a stroke, known in those days as “inflammation of the brain.” Caldwell County in Kentucky was named in his honor.

[Photo: John Caldwell Calhoun, fiery statesman (1782-1850)]

John Caldwell and Margaret Phillip’s youngest son, Rev. James Caldwell, was a hero in the Revolutionary War. James took an active role in military operations and his patriotism and fervor led the British to call him “The Black Rebel” and to his patriots “The Fighting Pastor.” He moved his family away from the parsonage but returned on occasion to preach to his congregation. A price was out on his head and he was often forced to preach with a loaded pistol lying on the pulpit. His wife, Hannah Ogden, was at home with their three youngest children and an eight month old infant when British soldiers arrived at her doorstep. She expressed confidence to her children that they would not do injury to them. To calm them she said, “They will respect a mother.” She was mistaken. A shot was fired through the window, it entered her chest and she was killed instantly by the “bloody hand of a British ruffian” right in front of her terrified children. The house was torched and reduced to ashes along with all their belongings. Fortunately, her children were spared.

A year later in 1781 James was also shot and killed, this time by an American sentinel who was thought to have been bribed by the British to do so. James left nine orphaned children. When his body was brought home many lined the streets and wept. The sentinel was convicted of murder and sentenced to death by hanging. Offers poured in from around the country to help take care of his children. Marquis de Lafayette took in one son and sent him to France to be educated. The future President of the Continental Congress Elias Boudinot gave assistance. General George Washington himself contributed $100.

[Photo: Hannah Ogden Caldwell]

John Caldwell and Margaret Phillip’s only daughter Margaret Caldwell married William Rodgers (1708-1750) in 1738. Their marriage certificate reports Margaret’s birthplace as Ireland in 1712. Records show that William was one of the early inhabitants of the Caldwell settlement. He died in October of 1750, within 14 days of the death of his father-in-law John Caldwell. His three children were all under the of six when he died. His wife remarried James Mitchell and had five more children.

William Rodgers and Margaret Caldwell’s first child was a daughter predictably named Margaret (1744-1808). She married a twin, Abraham Irwin, a “respectable man, though in moderate circumstances” at the age of 20. Abraham enlisted in the Revolutionary War effort in 1777 and marched to Dumfries, Virginia and when they were ordered to receive a smallpox vaccination, he refused his, believing he had already had smallpox as a child. Soon after he contracted the disease and died.

In the fall of 1782 Margaret moved to “the wilds of Kentucky” with a “number of enterprising Virginians.” At the close of the Revolutionary War the government gave grants of land as a reward for military service and a road opened up through Cumberland Gap in the Appalachians which made this move attractive despite the risks.

Three years later Margaret married Col. John Smith. John Smith had been captured by the Mohawks when he was 18 years old and was adopted by one of their tribes. He was initially terribly beaten when forced to run a gauntlet but recovered and subsequently was well treated. He managed to escape his captivity four years later. He used the skills he had learned to serve in the military and was commissioned as Colonel in command of the frontiers later in life. He also served in the Kentucky General Assembly.

Before dying in 1812, “after an illness of four weeks with an unspecified disease,” he authored a well-received book about his experiences as part of the tribe called “Remarkable Adventures in the Life and Times of Colonel James Smith.” According to James’ book, Margaret had a talent for writing children’s poetry and died in Bourbon County Kentucky in 1800. The odd portrait from the early 1800s of James that follows shows an unusual combination of cultural mixes.

William Rodgers and Margaret Caldwell also had a son named Andrew (1749-1825)of whom not much is known and a son named John, (1747-1836) who is my 5th great grandfather.

John Rodgers, the son of William Rodgers and Margaret Caldwell, was born 25 miles from the Caldwell Settlement.

He married Margaret Ann Daughtery (1748-1808). To highlight what a small world they lived in, her grandmother Anne Phillips Daughtery was the sister of John’s grandmother Margaret Phillips Caldwell. In other words John and Margaret were “kissing cousins.” John enlisted in the military in 1776 and served a two year term as a Corporal in the third Virginia regiment in the Revolutionary War.

He and his wife lived in the Caldwell Settlement area until 1781 when they ventured off to Kentucky and later to Franklin, Tennessee where William died. William was a surveyor and is said to have surveyed 12,000 acres of land along the Mississippi River. The first six of their children, including my 4th great grandfather William Caldwell Rodgers, were born in Virginia and another three were born in Kentucky.

[Photo:Col. James Smith (1737-1810)]

John Rodgers and Margaret Daughtery’s daughter Sarah (1786-1854) married Col. Randall William McGavock (1826-1863). Randal was an attorney, a Southern Planter, and a Colonel in the Civil War. He later became the Mayor of Nashville. In 1826 with the help of slave labor Randall built Carnton Plantation in Franklin, Tennessee. Randal was well connected; his good friend President Andrew Jackson visited him at his plantation on many occasions.

The Carnton Plantation, now a museum, was inherited by their son John and his wife Carrie Winder (1829-1905) who lived in it during the Battle of Franklin in the Civil War when it became a temporary field hospital for the wounded. More than 1,750 Confederate soldiers lost their lives during the battle in a town of less than 2,500 people. The bodies of four Confederate generals’ bodies killed during the fighting were laid out on their back porch.

Today the floors of the house are still stained from the blood that was shed in their home by the wounded and dying soldiers that filled every room in their home and spilled out onto their porches and lawns.

After the battle was over John donated two acres of land to be used as a cemetery for 1,500 of the soldiers. Carrie maintained a book of the dead, carefully cataloging the name of each dead soldier so they could be remembered. She wrote letters to their families and made daily walks in the cemetery grounds in her mourning clothes. She became the subject of a NY times bestselling novel in 2005 by Robert Hicks called the “The Widow of the South.”

[Photo: Confederate Cemetery, Carnton Plantation in the background"]

John Rodgers and Margaret Daughtery’s daughter Ann Phillips married Felix Grundy (1777-1840). Felix was a criminal attorney whose success drew large crowds when he served on the defense. He served as a Chief Justice for the Kentucky Court of Appeals, a Congressman, US Senator from Tennessee and the 13th US attorney general serving under President Van Buren. He was a law partner and mentor of James K Polk.

After his death four American counties were named for him in Illinois, Iowa, Missouri and Tennessee. His wife Ann organized a charitable society in Nashville that distributed Bibles and clothing to the poor of the city. She helped to found the “House of Industry for Females” which provided a home for orphan girls and gave them marketable domestic skills as an alternative to prostitution. She is also credited with starting the first Sunday school, featuring Bible studies as well as reading and spelling classes.

Local ministers refused to let her use their churches because her classes were “a violation of the Sabbath” because “teaching was inappropriate for a Sunday.” Sunday school, they claimed was “a scheme of the devil to capture the youth of the city.” Three years later they relented and Sunday school became acceptable. When she died in 1847 her obituary made no mention of her remarkable accomplishments. Instead she was “Mrs. Grundy, widow of the late Honorable Felix Grundy, a lady universally respected and beloved.”

John Rodgers and Margaret Daughtery’s daughter, Mary Eleanor, married Dr Stephen Chenault, who descended from a French Huguenot family that settled in America near Yorktown Virginia in 1701. Stephen fought with General Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812. After having seven children the family moved to Missouri and two more children were born. Stephen died in July of 1862. This is the first time the name Chenault appears in the family tree. Later it appears as the middle name in two of my ancestors so he must have left quite an impression on them.

John Rodgers and Margaret Daughtery’s first born son William Caldwell Rodgers (1771-1856) was my 4th great grandfather. He was born in Lunenberg County Virginia and was ten years old when his family moved to Kentucky. At the age of 22 he married Elizabeth “Betsy” Rutter (1775-1832). Together they had two daughters, Nancy Owen and Margaret Martin, and a son named Edmund Rutter, who is my 3rd great grandfather. In 1792 when Kentucky became a state, persons “possessed of a family and older than the age of 21” were entitled to land grants of 100 to 200 acres. William scooped up three grants, more than the normal amount perhaps because he “mustered in” to fight Native Americans in 1791. In 1806 he served as a Captain in the Corn Stalk Militia (so called because they used corn stalks for lack of guns to practice). Later in 1812 he was a member of the Kentucky Mounted Militia as part of an expedition to destroy Indian villages and their winter supplies. When he returned from this expedition he wrote a long searing letter to the editor of the Lexington Reporter to complain that “the foray was a fiasco. I have been 30 years this day a Citizen of Kentucky and I have experienced the danger and hardships of my fellow soldiers and I never before saw so much disorder in an Army from first to last as this one. ” Supplies were inadequate, horses were starving for lack of food, some horses were accidentally shot by their own men. In William’s view it was a disgrace, a waste of manpower and did not accomplish its purpose.

William Rodgers was the justice of the peace, the tax commissioner, and the surveyor for the County of Livingston in Kentucky. He built the courthouse and donated the land on which it stood to establish the Town of Salem, County Seat of Livingston County. An effort was made to impeach him in 1808 for improperly altering boundaries on a land grant survey and forging paperwork. William claimed he was innocent and that the man who initiated the impeachment was being vengeful due to a broken partnership deal. After a three day trail he was acquitted of wrongdoing. Five years after building the jail house, he was charged for failure to pay for some materials he had purchased to build it.

William also had troubles on the home front. In 1811 he sued his wife for a divorce on the grounds she had left his “bed and board and “all hopes of accommodation and her returning to him were gone.” He claimed that they had “lived in harmony with tenderness for each other for eight or nine years but after ten years he discovered in her a want of affection” and “that she had neglected her household duties.” She counterclaimed that she had been young when she married him, had never loved him and had “concealed in great measure the anguish of mind that tortured her existence,” and that since “her abandonment of his bed and board she has been much better satisfied with her life.” Although it was very unusual for the time, the court granted the divorce and ordered William to pay her $150 and a new woman’s side saddle. Based on his net worth these sums were very stingy. After the divorce, her whereabouts were unknown. The evidence suggests that their 14 year old son Edmund stayed with Betsy but that their two daughters aged 16 and 11 may have stayed with William. Three years after his divorce he married Jane Searcy – he was 43 and she was 17 years younger. Jane gave birth to two children.

Despite his divorce from Betsy, William retained a relationship with her family. Betsy’s sister Leticia (my 4th great grandaunt) was married to Lilburne Lewis. In 1812, when Lilburne was indicted for murder and his brother Ishan was indicted as an accessory, William helped to post the bond. William didn’t do this entirely out of the goodness of his heart, he used Lilburne slaves as collateral in case he skipped bond. Lilburne was accused of murdering a seventeen year old enslaved boy named George for breaking a pitcher belonging to his deceased mother. In a drunken rage Lilburne had killed him by tying him to a table and striking a lethal blow to his neck with an axe. He then forced one of the other enslaved persons to dismember the body and burn it in the fireplace. Unfortunately for Lilburne, an earthquake struck that night causing the chimney to collapse, and the unburnt bones were mortared inside when they rebuilt the chimney. Several months later another earthquake struck, crumbling the chimney once again, exposing the remains. A stray dog was found chewing on a skull which was identified as belonging to George because of a scar on his forehead. The two brothers knew they were in big trouble and made a suicide pact. Lewis shot himself but Ishan chickened out, was arrested, escaped, joined the Army under an assumed name and was killed in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. Lilburne made out his will prior to shooting himself and in it he referred to his wife Leticia three times as “beloved but cruel” and said he hoped to be reunited with his first wife in heaven. He left most of his estate for his six children and left Leticia four enslaved persons.

There are some strange ironies here. It’s okay to kidnap human beings and force them into slave labor. It’s okay to beat them if they don’t work hard enough, torture and hang them if they try to escape, rape their women, and keep them in abject misery. But it apparently is not okay to kill them if they break a water pitcher and turn them into a chimney. Afterall we are not heartless and we do have some lines that should not be crossed! And blaming his wife for being cruel in his will and wanting to reunite with his first wife? I am not even sure how to process that piece of information.

When William died at the age of 89 in 1856 he had outlived all five of his children and both of his wives but he did provide for his grandchildren. In the will stated that if his grandson, William Woodfin (the son of his daughter Margaret) was still living with him and taking care of him at the time he died that he would receive three slaves and one half of the land that he lived on. It appears he was a businessman right until the end.

Edmund Rutter Rodgers, the only son of William Caldwell Rodgers and Betsy Rutter, was born in 1797 in Washington County, Kentucky. He married Mary Phillips and had six children that lived to adulthood. Their first born child William Chenault Rodgers, my ancestor, was born in Kentucky. Their second child in Tennessee and the last four were born in Missouri. The genealogical trail that’s left of Edmund’s life is mostly a series of sales transactions. In 1827, he paid off a $400 loan from his father-in-law by giving him a seven year old mulatto child named Eliza and two mares. In 1840 he sold a 34 year old woman named Justine and her three year old daughter named Roseann for $800 as security for debt. The same year he sold an eleven year old named Martha, a nine year old named Adelaine, and a six year old named Henry for $1,000 as security for debt. In the 1840 tax list in Henry Tennessee, Edmund was listed as owning 100 acres of land valued at $500 and one enslaved person valued at $500. Edmund returned to Kentucky where he opened up the first dry goods store in Graves County. In 1845 he entered into a similar sales transaction involving six enslaved persons, also as security for debt. He died less than a year later in 1846 at age 49, leaving his widowed wife Mary with six children.

Edmund’s daughters seem to have done well for themselves. Ann Elizabeth (1821-1892) married an attorney, William Bradley. Sarah Moseley (1824-1906) married a merchant and stable keeper named Thomas L Morse. When she died at age 85 her obituary was entitled - “A Good Lady Dead,” and she was credited with having spent her whole life doing kind acts. Margaret Ann (1830-1896) married an Irish born surgeon named Andrew Wright, and she stayed by his side during the civil war to assist him. Though she was born in Missouri and died in Texas according to Margaret’s obit “it was to the old Kentucky home that her memory most fondly reverted.” The obit went on to say: “during the civil war she was sometimes thrown in with the Yankees soldiery and sometimes with the starving confederates and she met whatever fate befell her with the fearless courage, indomitable will and energy which characterized her whole life. Only the few that knew her most intimately were aware that for years her physical suffering had been almost unbearable. A less courageous spirit would have fainted under the burden long ago, but the unspeakable tenderness which she lavished on her family, the love she had for the sunshine and flowers, long kept the brave soul lingering in her frail little body.” Whoa. Too bad her sister hadn’t found the same person to put pen to paper.

Edmund’s son Harrison B. was born in 1835 and served as a captain in the civil war in the 2nd Kentucky Infantry. He was wounded and carried off the field in July of 1862 at the Battle of Murfreesboro in Tennessee. He recovered and nine months later he was killed in action in the battle of Chickamauga.

Edmund’s eldest son, William Chenault Rodgers (1820-1860) my 2nd great grandfather, was born in Tennessee. William made his living as a merchant. He married Martha Ann Wingo in the mid-1840s and they had three children. According to family legend he suffered from debilitating depression and on April 8, 1860 at the age of 40, he neatly folded all is clothes by the side of a river, walked into the water and drowned. The official cause of death on the death certificate was drowning but those close to him were convinced it was a suicide.

[Photo: William Chenault Rodgers and Martha Ann Wingo]

Their first child Edmund Rutter “Ed” was born in Feliciana Kentucky in 1848, married Susan Amanda Simmons, fathered four children and made his living as a dry goods merchant, a grocer and later in life as a rancher with 500 cattle in Texas.

Their second child William Chenault Jr. was born in 1854, married Mary Catherine “Kate” Ray, fathered seven children and owned a water powered grist mill. I was stunned to come across a newspaper article which reported that William Jr committed suicide in 1912. Since depression is an inherited trait it adds credence to the family’s claim that his father’s death was also a suicide.

William Chenault Rodgers Sr and Martha Ann Wingo’s third child, Charles W. Rodgers is my great grandfather. One of his children, Rosa Judson Rodgers, is my grandmother. Their stories are told elsewhere.

After her husband died, Martha Ann Wingo married a second time to a wealthy farmer, Jefferson Alexander. It was his third marriage. She outlived him and married a third time to James Nixon Hunter, a farm manager 17 years older than she was, who allegedly spent all of her money. She outlived James as well and moved in with her son Charles. She died in 1912.